A treatment for dry eye – a burning, gritty condition that can impair vision and damage the cornea – could some day result from computer simulations that map the way tears move across the surface of the eye.

Kara Maki, assistant professor in Rochester Institute of Technology’s School of Mathematical Sciences, contributed to a recent National Science Foundation study seeking to understand the basic motion of tear film traversing the eye. “Tear Film Dynamic with Evaporation, Wetting and Time Dependent Flux boundary Condition on an Eye-shaped Domain,” published in the journal Physics of Fluid, is an extension of Maki’s doctoral research under her thesis advisor and co-author Richard Braun, professor in the University of Delaware’s Department of Mathematical Sciences.

“We’re hoping if we can understand better the basic dynamics of the tear film, then we can start to understand what goes wrong if you have dry eye and start to think about potential cures by studying simulations,” Maki said.

Dry eye is a common condition without a cure. Many causes, including the aging process, contribute to discomfort resulting from either a lack of tears or tears that evaporate too quickly. In the United States alone, nearly 5 million people age 50 and older suffer from dry eye, according to the National Eye Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health. Women are predominantly afflicted with the condition, with more than 3 million diagnosed with dry eye due to hormonal changes associated with menopause. Treatment to alleviate symptoms includes eye drops and temporary or surgical plugs to stopper tear ducts at the inner corners of the eyes and retain fluid.

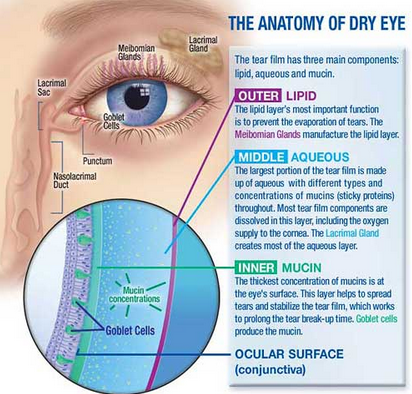

To understand dry eye, Maki had to begin with the physics and chemistry of tears. Tear film consists of a layer of water sandwiched between an oily layer of lipids on the outside to prevent evaporation and an inner mucous layer to spread the water over the eye.

Kara developed a mathematical model to simulate the direction tear film travels when entering the eye from the lacrimal glands above the upper eyelid. Using the software program Overture, she recreated the flow of tears on the surface of an open eye, moving from the upper corner and draining through the ducts at the opposite corner.

“One thing we were able to find is that when your eyes are open, the tears get thin right along the edge of the eye, and that is referred to as the ‘black line,'” Maki said. “That has been seen clinically and can be reproduced in our simulations.”

The tears, Maki explains, climb up the eyelid and join a column of fluid that travels along the lids. Lower pressure sucks the fluid into the meniscus and away from the center, creating the black line and dry spots in the tear film that can compromise vision and irritate the cornea.

Maki saturated the eye with liquid to penetrate the black line. She wanted to know if the fluid would travel down the front of the eye and relieve the thinning of the tear film.

“We found that we had to really flood the eye in our simulations. The fluid would rather travel in the meniscus,” Maki said. “It splits traveling along the upper lid and the lower lid. We confirmed that blinking is necessary to stop this thinning from happening. Every time you blink, the tear film gets repainted on the front of your eye. It’s important to have smooth tear film for optical quality.”The next step for Maki and the team led by Braun is to simulate the dynamics of tear films in a blinking eye.

“The nice thing about having a model is that you can make unrealistic things happen,” Maki said. “For example, we can flood the eye and see where the tears go. Or we can look at what happens when the drainage holes are plugged. Where does the fluid go? You can start to explore these things in a safe way.”

http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/releases/277495.php

Picture courtesy to www.optometrystudents.com